Göttliche Entität, oberstes Wesen und Hauptobjekt des Glaubens

Im monotheistischen Denken wird Gott als das höchste Wesen, die Schöpfergottheit und das wichtigste Objekt des Glaubens verstanden. [3] Die von Theologen beschriebenen Vorstellungen von Gott umfassen im Allgemeinen die Attribute Allwissenheit (Allwissen), Allmacht (Allmacht), Allgegenwart (Allgegenwart) und eine ewige und notwendige Existenz. Je nach Art des Theismus werden diese Attribute entweder analog oder im wörtlichen Sinne als bestimmte Eigenschaften verwendet. Gott wird am häufigsten als unkörperlich (als immateriell) bezeichnet. [3][4][5] Unkörperlichkeit und Körperlichkeit Gottes stehen im Zusammenhang mit Vorstellungen von Transzendenz (außerhalb der Natur zu sein) und Immanenz (in der Natur zu sein) von Gott, mit Positionen der Synthese wie dem "Immanenten" Transzendenz". Der Psychoanalytiker Carl Jung setzte religiöse Vorstellungen von Gott in seiner Interpretation mit transzendentalen Aspekten des Bewusstseins gleich. [6]

Einige Religionen beschreiben Gott ohne Bezug zum Geschlecht, während andere oder deren Übersetzungen geschlechtsspezifische Terminologie verwenden. Das Judentum schreibt Gott nur ein grammatikalisches Geschlecht zu, indem er Bezeichnungen wie "Ihn" oder "Vater" verwendet. [7]

Gott wurde entweder als persönlich oder unpersönlich konzipiert. Im Theismus ist Gott der Schöpfer und Erhalter des Universums, während Gott im Deismus der Schöpfer des Universums ist, nicht aber der Erhalter. Im Pantheismus ist Gott das Universum selbst. Im Atheismus fehlt der Glaube an Gott. Im Agnostizismus wird die Existenz Gottes als unbekannt oder unkenntlich betrachtet. Gott wurde auch als die Quelle aller sittlichen Verpflichtung konzipiert und als "das denkbar größte Bestehen". [3] Viele namhafte Philosophen haben Argumente für und gegen die Existenz Gottes entwickelt. [8]

Monotheisten beziehen sich auf ihre Götter mit Namen, die von vorgeschrieben sind ihre jeweiligen Religionen, wobei sich einige dieser Namen auf bestimmte kulturelle Vorstellungen von der Identität und den Eigenschaften ihres Gottes beziehen. In der ägyptischen Ära des Atenismus, der möglicherweise ältesten aufgezeichneten monotheistischen Religion, hieß diese Gottheit Aten [9] . Sie sollte das "wahre" Oberste Wesen und der Schöpfer des Universums sein. [10] In der hebräischen Bibel und im Judentum Elohim, Adonai, YHWH (hebräisch: יהוה ) und andere Namen werden als Namen Gottes verwendet. Jahwe und Jehova, mögliche Lautäußerungen von JHWH, werden im Christentum verwendet. In der christlichen Lehre von der Dreieinigkeit wird Gott, der in drei "Personen" besteht, Vater, Sohn und Heiliger Geist genannt. Im Islam wird der Name Allah verwendet, während Muslime eine Vielzahl von Titelnamen für Gott haben. Im Hinduismus wird Brahman oft als ein monistisches Konzept von Gott betrachtet. [11] In der chinesischen Religion wird Shangdi als Vorläufer (erster Vorfahre) des Universums verstanden, das ihm innewohnt und ständig Ordnung bringt. Andere Religionen haben Namen für das Konzept, zum Beispiel Baha im Bahá'í-Glauben, [12] Waheguru im Sikhismus, [13] Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa im balinesischen Hinduismus, [14] und Ahura Mazda im Zoroastrianismus. [15]

Viele unterschiedliche Vorstellungen von Gott und konkurrierende Behauptungen hinsichtlich der Merkmale, Ziele und Handlungen Gottes haben zur Entwicklung von Vorstellungen von Omnitheismus, Pandeismus [16] oder einer mehrjährigen Philosophie geführt, in der die theologische Wahrheit zugrunde liegt was alle Religionen ein partielles Verständnis ausdrücken, und darüber, "was die Gläubigen in den verschiedenen großen Weltreligionen tatsächlich diesen einen Gott anbeten, aber durch unterschiedliche, überlappende Begriffe". [17]

Etymologie und Gebrauch

Die älteste geschriebene Form des germanischen Wortes God stammt aus dem 6. Jahrhundert des Christlichen Codex Argenteus . Das englische Wort selbst leitet sich vom Proto-Germanischen * ǥuđan ab. Die rekonstruierte Proto-Indo-Europäische Form * ǵhu-tó-m basierte wahrscheinlich auf der Wurzel * ǵhau (ə) - was entweder "aufrufen" oder "aufrufen" bedeutete ". [18] Die germanischen Wörter für God waren ursprünglich sächsisch - auf beide Geschlechter zutreffend -, aber während des Christianisierungsprozesses der germanischen Völker aus ihrem einheimischen germanischen Heidentum wurden die Worte zu einer männlichen syntaktischen Form. [19]

In englischer Sprache wird die Großschreibung für Namen verwendet, unter denen ein Gott bekannt ist, einschließlich "Gott". [20] Folglich wird die Großschreibung des Gottes nicht für mehrere Götter verwendet (Polytheismus). oder wenn verwendet wird, um auf die generische Idee einer Gottheit zu verweisen. [21][22]

Das englische Wort God und seine Gegenstücke in anderen Sprachen werden normalerweise für alle und alle Vorstellungen verwendet und trotz erheblicher Unterschiede zwischen den Religionen Der Begriff bleibt eine englische Übersetzung, die allen gemeinsam ist. Dasselbe gilt für hebräisch el aber im Judentum erhält Gott auch einen eigenen Namen, das Tetragrammaton YHWH, dessen Ursprung möglicherweise der Name einer edomitischen oder midianitischen Gottheit, Jahwe, ist.

Wenn in vielen Übersetzungen der Bibel das Wort LORD in allen Hauptstädten steht, bedeutet dies, dass das Wort das Tetragrammaton darstellt. [23]

Allāh (Arabisch: الله ) ist der arabische Begriff ohne Plural, der von Muslimen und arabisch sprechenden Christen und Juden verwendet wird, was "Der Gott" bedeutet (wobei der erste Buchstabe groß geschrieben wird), während "ʾilāh" (arabisch: إله ) der verwendete Begriff ist eine Gottheit oder ein Gott im Allgemeinen. [24][25][26] Gott kann auch einen eigenen Namen in monotheistischen Strömungen des Hinduismus gegeben werden, die die persönliche Natur Gottes betonen, wobei früh auf seinen Namen als Krishna-Vasudeva in Bhagavata oder später Vishnu und Hari Bezug genommen wird. [27]

Ahura Mazda ist der im Zoroastrianismus verwendete Name für Gott. "Mazda", oder besser die avestanische Stammform Mazdā- Nominativ Mazdå spiegelt Proto-Iraner * Mazdāh (weiblich) wider. Es wird allgemein angenommen, dass es der richtige Name des Geistes ist, und wie sein Sanskrit verwandter medh bedeutet "Intelligenz" oder "Weisheit". Sowohl das Avestanische als auch das Sanskrit-Wort spiegeln Proto-Indo-Iraner * mazdhā- wider, von Proto-Indo-European Mn̩sdʰeh 1 wörtlich übersetzt "Platzieren [ dʰeh 1 ) der Verstand ( * mn̩-s ) ", daher" weise ".

Waheguru ( Punjabi: vāhigurū ) wird am häufigsten verwendet Sikhismus, um sich auf Gott zu beziehen. Es bedeutet "wunderbarer Lehrer" in der Punjabi-Sprache. Vāhi (eine mittelpersische Anleihe) bedeutet "wunderbar" und guru ( Sanskrit: guru ) ist ein Begriff, der "Lehrer" bedeutet. Waheguru wird von einigen auch als eine Erfahrung der Ekstase beschrieben, die über alle Beschreibungen hinausgeht. Die häufigste Verwendung des Wortes "Waheguru" ist die Begrüßung, die Sikhs miteinander verwenden:

Waheguru Ji Ka Khalsa, Waheguru Ji Ki Fateh

Khalsa des wunderbaren Herrn, der Sieg geht an den wunderbaren Herrn.

Baha der "größte" Name für Gott im Bahá'í-Glauben, ist arabisch für "All-Glorious".

Allgemeine Vorstellungen

Es gibt keinen klaren Konsens über das Wesen oder die Existenz Gottes. [29] Die abrahamischen Vorstellungen von Gott umfassen die monotheistische Definition von Gott im Judentum, die Trinität der Christen und die islamische Auffassung von Gott. Die dharmischen Religionen unterscheiden sich in ihrer Sicht des Göttlichen: Gottes Ansichten im Hinduismus unterscheiden sich je nach Region, Sekte und Kaste von monotheistisch bis polytheistisch. Viele polytheistische Religionen teilen die Vorstellung einer Schöpfergottheit, obwohl sie einen anderen Namen als "Gott" hat und nicht alle anderen Rollen hat, die monotheistischen Religionen einem einzigen Gott zugeschrieben werden. Jainismus ist polytheistisch und nicht kreationistisch. Je nach Interpretation und Tradition kann der Buddhismus entweder als atheistisch, nicht-theistisch, pantheistisch, panentheistisch oder polytheistisch verstanden werden.

Einssein

Monotheisten behaupten, dass es nur einen Gott gibt, und können behaupten, dass der eine wahre Gott in verschiedenen Religionen unter verschiedenen Namen verehrt wird. Die Ansicht, dass alle Theisten tatsächlich denselben Gott verehren, ob sie es nun wissen oder nicht, wird besonders im Bahá'í-Glauben, im Hinduismus [30] und im Sikhismus [31]

hervorgehoben. Die Trinitätslehre beschreibt Gott als einen Gott in drei göttlichen Personen (jede der drei Personen ist Gott selbst). Die Allerheiligsten Dreieinigkeit umfasst [32] Gott den Vater, Gott den Sohn (welcher Jesus Christus Gott ist) und Gott den Heiligen Geist. In den vergangenen Jahrhunderten wurde dieses grundlegende Mysterium des christlichen Glaubens auch von der lateinischen Formel Sancta Trinitas, Unus Deus (Heilige Dreifaltigkeit, einzigartiger Gott) zusammengefasst, über die Litanias Lauretanas berichtet.

Das grundlegendste Konzept des Islam ist tawhid (Bedeutung für "Einheit" oder "Einzigartigkeit"). Gott wird im Quran beschrieben als: "Sprich: Er ist Allah, der Einzige und Einzige; Allah, der Ewige, Absolute; Er zeugt nicht und wird auch nicht gezeugt; Und es gibt keinen, der ihm ähnlich ist." [33][34] Muslime lehnen dies ab die christliche Lehre von der Dreieinigkeit und der Gottheit Jesu, verglichen mit dem Polytheismus. Im Islam ist Gott transzendent und ähnelt in keiner Weise seinen Schöpfungen. Daher sind Muslime keine Ikonodulen und es wird nicht erwartet, dass sie Gott visualisieren. [35]

Der Henotheismus ist der Glaube und die Verehrung eines einzigen Gottes, während er die Existenz oder mögliche Existenz anderer Gottheiten akzeptiert. [19659050] Theismus, Deismus und Pantheismus

Theismus behauptet allgemein, dass Gott realistisch, objektiv und unabhängig vom menschlichen Denken existiert; dass Gott alles geschaffen hat und erhält; dass Gott allmächtig und ewig ist; und dass Gott persönlich ist und mit dem Universum interagiert, zum Beispiel durch religiöse Erfahrung und die Gebete der Menschen. [37] Theismus behauptet, dass Gott sowohl transzendent als auch immanent ist; so ist Gott gleichzeitig unendlich und in gewisser Weise in den Angelegenheiten der Welt präsent. [38] Nicht alle Theisten unterschreiben alle diese Sätze, aber jeder schließt gewöhnlich einige von ihnen an (vergleiche dazu die Familie) Ähnlichkeit). [37] Die katholische Theologie besagt, dass Gott unendlich einfach ist und nicht unfreiwillig der Zeit unterliegt. Die meisten Theisten glauben, dass Gott allmächtig, allwissend und wohlwollend ist, obwohl dieser Glaube die Frage nach Gottes Verantwortung für das Böse und Leid in der Welt aufwirft. Einige Theisten schreiben Gott eine selbstbewusste oder gezielte Begrenzung von Allmacht, Allwissenheit oder Wohlwollen vor. Offener Theismus dagegen behauptet, dass Gottes Allwissenheit aufgrund der Natur der Zeit nicht bedeutet, dass die Gottheit die Zukunft vorhersagen kann. Theismus wird manchmal verwendet, um allgemein auf irgendeinen Glauben an einen Gott oder Götter, dh Monotheismus oder Polytheismus, zu verweisen. [39][40]

Deism ist der Ansicht, dass Gott vollständig transzendent ist: Gott existiert, greift aber nicht in das Jenseits ein, was für seine Erschaffung notwendig war. [38] In dieser Ansicht ist Gott nicht anthropomorph und er beantwortet keine Gebete noch Wunder produziert. Im Deismus üblich ist der Glaube, dass Gott kein Interesse an der Menschheit hat und sich der Menschheit nicht einmal bewusst ist. Pandeism kombiniert Deism mit pantheistischen Überzeugungen. [16][41][42] Pandeism wird vorgeschlagen, um zu erklären, warum Gott ein Universum erschaffen und dann aufgeben würde, [43] und hinsichtlich des Pantheismus den Ursprung und Zweck des Universums. [43] [44]

Der Pantheismus hält Gott für das Universum und das Universum für Gott, während der Panentheismus für Gott das Universum enthält, aber nicht mit ihm identisch ist. [45] Es ist auch die Ansicht der liberal-katholischen Kirche; Theosophie; einige Ansichten des Hinduismus mit Ausnahme des Vaishnavismus, der an Panentheismus glaubt; Sikhismus; einige Abteilungen des Neopaganismus und des Taoismus, zusammen mit vielen unterschiedlichen Konfessionen und Individuen innerhalb der Konfessionen. Kabbala, jüdischer Mystizismus, malt eine pantheistische / panentheistische Sicht von Gott, die im chassidischen Judentum breite Akzeptanz findet, insbesondere von ihrem Gründer The Baal Shem Tov - aber nur als Ergänzung zur jüdischen Sicht eines persönlichen Gottes, nicht im ursprünglichen Pantheismus Sinn, das Persona auf Gott leugnet oder einschränkt Zitat benötigt

Andere Begriffe

Der Dystheismus, der mit der Theodize zusammenhängt, ist eine Form des Theismus, die besagt, dass Gott entweder nicht ist ganz gut oder völlig bösartig als Folge des Problems des Bösen. Ein solches Beispiel stammt aus Dostojewskis The Brothers Karamazov in dem Iwan Karamazov Gott mit der Begründung ablehnt, dass er Kinder leiden lässt. [46]

In der heutigen Zeit einige mehr Es wurden abstrakte Konzepte entwickelt, wie Prozesstheologie und offener Theismus. Der zeitgenössische französische Philosoph Michel Henry hat jedoch eine phänomenologische Herangehensweise und Definition von Gott als phänomenologisches Wesen des Lebens vorgeschlagen. [19459105[47]

Gott wurde auch als unkörperliches (immaterielles) Wesen, die Quelle aller moralischen Verpflichtung und die "größte denkbare Existenz". [3] Diese Eigenschaften wurden alle in unterschiedlichem Ausmaß von den frühen jüdischen, christlichen und muslimischen Theologen, einschließlich Maimonides, [48] Augustine of Hippo, [48] unterstützt. und Al-Ghazali [8] .

Nichttheistische Ansichten

Nichttheistische Ansichten über Gott unterscheiden sich auch. Einige Nicht-Theisten meiden den Begriff von Gott, akzeptieren jedoch, dass dies für viele von Bedeutung ist. andere Nicht-Theisten verstehen Gott als Symbol menschlicher Werte und Bestrebungen. Der englische Atheist Charles Bradlaugh aus dem 19. Jahrhundert erklärte, er habe sich geweigert, "Es gibt keinen Gott" zu sagen, weil "das Wort" Gott "für mich ein Ton ist, der keine eindeutige oder eindeutige Aussage vermittelt", [49] er sagte genauer ungläubig an den christlichen Gott. Stephen Jay Gould schlug einen Ansatz vor, der die Welt der Philosophie in sogenannte "nicht überlappende Magisterien" (NOMA) unterteilt. Fragen des Übernatürlichen, wie etwa die Existenz und Natur Gottes, sind aus dieser Sicht nicht empirisch und die eigentliche Domäne der Theologie. Die Methoden der Wissenschaft sollten dann zur Beantwortung jeder empirischen Frage über die natürliche Welt verwendet werden, und die Theologie sollte zur Beantwortung von Fragen über die letztendliche Bedeutung und den moralischen Wert verwendet werden. In dieser Ansicht macht das Fehlen eines empirischen Fußabdrucks aus dem Lehramt des Übernatürlichen auf Naturereignisse die Wissenschaft zum einzigen Akteur der Natur. [50]

Eine andere Ansicht, die von Richard Dawkins vertreten wurde, ist, dass die Existenz Gottes eine empirische Frage ist, mit der Begründung, dass "ein Universum mit einem Gott eine völlig andere Art von Universum sei als ein Universum, und es wäre ein wissenschaftlicher Unterschied." [51] Carl Sagan argumentierte, dass Die Doktrin eines Schöpfers des Universums war schwer zu beweisen oder zu widerlegen, und die einzige denkbare wissenschaftliche Entdeckung, die die Existenz eines Schöpfers (nicht notwendigerweise eines Gottes) widerlegen könnte, wäre die Entdeckung, dass das Universum unendlich alt ist. [52]

Stephen Hawking und Co-Autor Leonard Mlodinow stellen in ihrem Buch The Grand Design fest, dass es sinnvoll ist zu fragen, wer oder was das Universum geschaffen hat, aber ob die Antwort Gott ist. dann die Fragen Die bloße Verwerfung wurde lediglich zu derjenigen abgelenkt, von der Gott geschaffen wurde. Beide Autoren behaupten jedoch, dass es möglich ist, diese Fragen rein wissenschaftlich zu beantworten, ohne göttliche Wesen anzurufen. [53]

Agnostizismus und Atheismus

Agnostizismus ist die Ansicht, dass die Wahrheitswerte bestimmter Ansprüche - insbesondere metaphysisch - gelten und religiöse Behauptungen, ob Gott, der Göttliche oder das Übernatürliche existieren, sind unbekannt und vielleicht nicht bekannt. [54] [55] [56] [19456522]

] Atheismus ist im weitesten Sinne die Ablehnung des Glaubens an die Existenz von Gottheiten. [57][58] Atheismus ist im engeren Sinne die Position, dass es keine Gottheiten gibt. [59]

Anthropomorphismus

Pascal Boyer argumentiert dies während Es gibt eine Vielzahl von übernatürlichen Konzepten auf der ganzen Welt. Im Allgemeinen neigen übernatürliche Wesen dazu, sich ähnlich wie Menschen zu verhalten. Die Konstruktion von Göttern und Geistern wie Personen ist eines der bekanntesten Merkmale der Religion. Er zitiert Beispiele aus der griechischen Mythologie, die seiner Meinung nach eher einer modernen Seifenoper als anderen religiösen Systemen ähnelt. [60] Bertrand du Castel und Timothy Jurgensen demonstrieren durch Formalisierung, dass Boyers Erklärungsmodell mit der Epistemologie der Physik übereinstimmt, wenn es nicht direkt beobachtbar ist Entitäten als Vermittler. [61] Der Anthropologe Stewart Guthrie behauptet, dass Menschen menschliche Merkmale auf nicht-menschliche Aspekte der Welt projizieren, weil sie diese Aspekte vertrauter machen. Sigmund Freud meinte auch, Gottes Konzepte seien Projektionen des eigenen Vaters. [62]

Ebenso war Émile Durkheim einer der ersten, der darauf hindeutete, dass Götter eine Erweiterung des menschlichen Lebens darstellen und übernatürliche Wesen einschließen. Entsprechend dieser Argumentation behauptet der Psychologe Matt Rossano, dass Menschen, als sie in größeren Gruppen zu leben begannen, Götter geschaffen haben könnten, um die Moral durchzusetzen. In kleinen Gruppen kann die Moral durch soziale Kräfte wie Klatsch oder Reputation erzwungen werden. Es ist jedoch viel schwieriger, die Moral durch soziale Kräfte in viel größeren Gruppen durchzusetzen. Rossano weist darauf hin, dass die Menschen durch die Einbeziehung immer wachsamer Götter und Geister eine wirksame Strategie zur Eindämmung des Egoismus und zum Aufbau kooperativer Gruppen gefunden haben. [63]

Existenz

Zahllose Argumente wurden vorgeschlagen, um die Existenz Gottes zu beweisen. [65] Einige der bemerkenswertesten Argumente sind die fünf Wege von Aquin, das Argument von Sehnsucht von CS Lewis und das von St. Anselm und René Descartes formulierte ontologische Argument [66]

St. Anselms Ansatz bestand darin, Gott als "das zu definieren, worüber nichts Größeres gedacht werden kann". Der berühmte pantheistische Philosoph Baruch Spinoza würde diese Idee später bis zum Äußersten ausdrücken: "Unter Gott verstehe ich ein Wesen, das absolut unendlich ist, d. H. Eine Substanz, die aus unendlichen Attributen besteht, von denen jeder eine ewige und unendliche Essenz ausdrückt." Für Spinoza besteht das gesamte natürliche Universum aus einer Substanz, Gott oder seiner Entsprechung, der Natur. [67] Sein Beweis für die Existenz Gottes war eine Variation der ontologischen Argumentation. [68]

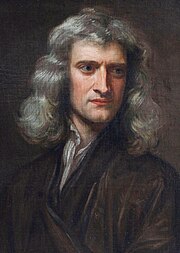

Der Wissenschaftler Isaac Newton sah das Nichttinitarielle Gott [69] als meisterhafter Schöpfer, dessen Existenz angesichts der Größe aller Schöpfung nicht geleugnet werden konnte. [70] Trotzdem wies er die These von Polymath Leibniz zurück, Gott würde notwendigerweise eine vollkommene Welt schaffen, die kein Eingreifen des Schöpfers erfordert . In Frage 31 der Opticks argumentierte Newton gleichzeitig mit dem Design und der Notwendigkeit einer Intervention:

Während Kometen sich in sehr exzentrischen Kugeln in allen möglichen Stellungen bewegen, konnte das blinde Schicksal niemals alles machen Die Planeten bewegen sich in konzentrischen Orben ein und dieselbe Weise, mit Ausnahme einiger unwesentlicher Unregelmäßigkeiten, die möglicherweise aus dem Zusammenwirken von Kometen und Planeten aufeinander entstanden sind und die wahrscheinlich zunehmen werden, bis dieses System eine Reformation wünscht. [71]

St. Thomas glaubte, dass die Existenz Gottes in sich selbst selbstverständlich ist, aber nicht für uns. "Deshalb sage ich, dass dieser Satz" Gott existiert "von selbst selbstverständlich ist, denn das Prädikat ist das gleiche wie das Subjekt ... Nun, da wir das Wesen Gottes nicht kennen, ist der Satz nicht selbst. für uns offensichtlich, muss aber durch etwas bewiesen werden, das uns bekannter ist, obwohl es in seiner Natur weniger bekannt ist - nämlich durch Wirkungen. "[72]

St. Thomas glaubte, dass die Existenz Gottes bewiesen werden kann. Kurz in den Summa theologiae und ausführlicher in den Summa contra Gentiles betrachtete er ausführlich fünf Argumente für die Existenz Gottes, die weithin als quinque viae bekannt sind ] (Five Ways).

- ] Bewegung: Einige Dinge bewegen sich zweifellos, können jedoch keine eigenen Bewegungen verursachen. Da es keine unendliche Kette von Bewegungsursachen geben kann, muss es einen First Mover geben, der nicht durch etwas anderes bewegt wird, und das ist es, was jeder unter Gott versteht.

- Ursache: Wie bei Bewegung kann nichts sich selbst verursachen. und eine unendliche Kette der Kausalität ist unmöglich, daher muss es eine erste Ursache geben, die Gott genannt wird.

- Existenz von Notwendigem und Unnötigem: Unsere Erfahrung beinhaltet Dinge, die zwar vorhanden, aber anscheinend unnötig sind. Es kann nicht alles unnötig sein, denn dann war einmal nichts und es würde immer noch nichts geben. Wir sind daher gezwungen, etwas Notwendiges anzunehmen, das diese Notwendigkeit nur aus sich selbst hat; in der Tat selbst ist der Grund dafür, dass andere Dinge existieren.

- Abstufung: Wenn wir eine Abstufung der Dinge in dem Sinne feststellen können, dass einige Dinge heißer, guter usw. sind, muss es einen Superlativ geben, der der wahrste und edelste ist Sache, und so am vollständigsten vorhanden. Wir bezeichnen dies als Gott (Anmerkung: Thomas schreibt Gott keine tatsächlichen Eigenschaften zu.)

- Geordnete Tendenzen der Natur: In allen Körpern wird eine Richtung des Handelns zu einem Ende verfolgt, die den Naturgesetzen folgt. Alles ohne Bewusstsein neigt zu einem Ziel unter der Führung eines Bewusstseins. Dies nennen wir Gott (man beachte, dass selbst wenn wir Objekte leiten, in Thomas die Quelle unseres gesamten Wissens auch von Gott stammt). [73]

Einige Theologen, wie der Wissenschaftler und Theologe AE McGrath, behaupten, die Existenz von Gott ist keine Frage, die mit der wissenschaftlichen Methode beantwortet werden kann. [74][75] Der Agnostiker Stephen Jay Gould argumentiert, dass Wissenschaft und Religion nicht in Konflikt stehen und sich nicht überschneiden. [76]

Einige Befunde in Die Gebiete der Kosmologie, der Evolutionsbiologie und der Neurowissenschaften werden von einigen Atheisten (einschließlich Lawrence M. Krauss und Sam Harris) als Beweis dafür interpretiert, dass Gott nur eine imaginäre Entität ohne wirkliche Grundlage ist. [77][78] Diese Atheisten behaupten, Der allwissende Gott, der das Universum geschaffen hat und besonders auf das Leben der Menschen aufmerksam ist, wurde generationenübergreifend vorgestellt, verschönert und verbreitet. [79] Richard Dawkins interpretiert solche Erkenntnisse nicht nur als einen Mangel an Beweise für die materielle Existenz eines solchen Gottes, aber als umfassende Beweise für das Gegenteil. [50] Einige Theologen und Wissenschaftler, darunter Alister McGrath, widersprechen jedoch seiner Auffassung, dass die Existenz Gottes mit der Wissenschaft vereinbar ist. [80]

Spezifische Attribute

Unterschiedliche religiöse Traditionen weisen Gott unterschiedliche (wenn auch oft ähnliche) Attribute und Merkmale zu, einschließlich expansiver Kräfte und Fähigkeiten, psychologischer Merkmale, Geschlechtermerkmale und bevorzugter Nomenklatur. Die Zuordnung dieser Attribute unterscheidet sich häufig nach den Vorstellungen von Gott in der Kultur, aus der sie stammen. Zum Beispiel haben Attribute des Gottes im Christentum, Attribute des Gottes im Islam und die dreizehn Attribute der Barmherzigkeit im Judentum gewisse Ähnlichkeiten, die sich aus ihren gemeinsamen Wurzeln ergeben.

Names

Das Wort God ist "eines der komplexesten und schwierigsten in der englischen Sprache". In der jüdisch-christlichen Tradition war "die Bibel die Hauptquelle der Vorstellungen von Gott". Dass die Bibel "viele verschiedene Bilder, Konzepte und Denkweisen über" Gott hat zu ewigen "Meinungsverschiedenheiten darüber geführt, wie Gott gedacht und verstanden werden soll". [81]

Im gesamten Hebräisch und christliche Bibeln gibt es viele Namen für Gott. Einer von ihnen ist Elohim. Eine andere ist El Shaddai übersetzt "God Allmächtiger". [82] Ein dritter bemerkenswerter Name ist El Elyon was "Der Hohe Gott" bedeutet. [83] [83].

Gott wird im Koran und im Hadith mit bestimmten Namen oder Attributen beschrieben und bezeichnet, wobei der häufigste Al-Rahman ("Most Compassionate") und Al-Rahim der Begriff "Most Chariful" bedeutet "(Siehe Namen Gottes im Islam). [84]

Viele dieser Namen werden auch in den Schriften des Bahá'í-Glaubens verwendet.

Viele Traditionen sehen Gott als unkörperlich und ewig an und betrachten ihn als einen Punkt, an dem Licht wie menschliche Seelen lebt, aber ohne physischen Körper, da er nicht in den Zyklus von Geburt, Tod und Wiedergeburt eintritt. Gott wird als die perfekte und beständige Verkörperung aller Tugenden, Kräfte und Werte gesehen und er ist der bedingungslos liebende Vater aller Seelen, unabhängig von ihrer Religion, ihrem Geschlecht oder ihrer Kultur. [19459554

Der Vaishnavismus, eine Tradition im Hinduismus, hat eine Liste von Titeln und Namen von Krishna.

Geschlecht

Geschlecht

Das Geschlecht Gottes kann entweder als buchstäblicher oder als allegorischer Aspekt einer Gottheit betrachtet werden, der in der klassischen westlichen Philosophie die körperliche Form überschreitet. [86][87] Polytheistische Religionen schreiben gewöhnlich jede der zu Götter ein Geschlecht, das es jedem ermöglicht, mit jedem anderen, und vielleicht auch mit Menschen, sexuell zu interagieren. In den meisten monotheistischen Religionen hat Gott kein Gegenüber, mit dem er sich sexuell beziehen kann. In der klassischen westlichen Philosophie ist das Geschlecht dieser einzigen Gottheit höchstwahrscheinlich eine analoge Aussage darüber, wie Menschen und Gott einander ansprechen und miteinander in Beziehung stehen. Gott wird nämlich als Züchter der Welt und Offenbarung betrachtet, die der aktiven (im Gegensatz zur rezeptiven) Rolle im Geschlechtsverkehr entspricht. [88]

Biblische Quellen beziehen sich normalerweise auf Gott, indem sie männliche Wörter verwenden außer Genesis 1: 26–27, [89][90] Psalm 123: 2–3 und Lukas 15: 8–10 (weiblich); Hosea 11: 3,4, Deuteronomium 32:18, Jesaja 66:13, Jesaja 49:15, Jesaja 42:14, Psalm 131: 2 (eine Mutter); Deuteronomium 32: 11–12 (Mutteradler); und Matthäus 23:37 und Lukas 13:34 (eine Mutterhenne).

Beziehung zur Schöpfung

Das Gebet spielt bei vielen Gläubigen eine bedeutende Rolle. Muslime glauben, dass der Zweck der Existenz darin besteht, Gott anzubeten. [91][92] Er wird als persönlicher Gott betrachtet, und es gibt keine Vermittler wie Klerus, um mit Gott in Kontakt zu treten. Zum Gebet gehören oft auch Bittgebete und um Vergebung. Gott glaubt oft, dass er verzeiht. Ein Hadith besagt zum Beispiel, Gott würde ein sündloses Volk durch eines ersetzen, das sündigte, aber die Umkehr forderte. [93] Der christliche Theologe Alister McGrath schreibt, dass es gute Gründe gibt, anzunehmen, dass ein "persönlicher Gott" ein integraler Bestandteil der christlichen Einstellung ist, aber dass man verstehen muss, dass es eine Analogie ist. "Zu sagen, dass Gott wie eine Person ist, bedeutet, die göttliche Fähigkeit und Bereitschaft, sich auf andere zu beziehen, zu bestätigen. Dies bedeutet nicht, dass Gott ein Mensch ist oder sich an einem bestimmten Punkt im Universum befindet." [94]

Anhänger verschiedener Religionen sind sich im Allgemeinen nicht einig darüber, wie Gott am besten angebetet werden kann und was Gottes Plan für die Menschheit ist, wenn es einen gibt. Es gibt unterschiedliche Ansätze, die widersprüchlichen Ansprüche monotheistischer Religionen miteinander in Einklang zu bringen. Eine Ansicht wird von Exklusivisten vertreten, die sich für das auserwählte Volk halten oder exklusiven Zugang zur absoluten Wahrheit haben, im Allgemeinen durch Offenbarung oder Begegnung mit dem Göttlichen, was Anhänger anderer Religionen nicht tun. Eine andere Ansicht ist religiöser Pluralismus. Ein Pluralist glaubt typischerweise, dass seine Religion die richtige ist, bestreitet aber nicht die partielle Wahrheit anderer Religionen. Ein Beispiel für eine pluralistische Sichtweise im Christentum ist der Supersessionismus, d. H. Der Glaube, dass die eigene Religion die Erfüllung vorhergehender Religionen ist. Ein dritter Ansatz ist der relativistische Inklusivismus, bei dem jeder als gleichermaßen richtig gilt. Ein Beispiel ist der Universalismus: Die Lehre, dass die Erlösung letztendlich für alle verfügbar ist. Ein vierter Ansatz ist der Synkretismus, der verschiedene Elemente aus verschiedenen Religionen vermischt. Ein Beispiel für Synkretismus ist die New Age-Bewegung.

Juden und Christen glauben, dass Menschen nach dem Ebenbild Gottes geschaffen wurden und das Zentrum, die Krone und der Schlüssel zu Gottes Schöpfung sind, Verwalter für Gott, über alles andere, was Gott gemacht hatte ( Gen 1:26 ) ]); Aus diesem Grund werden Menschen im Christentum als "Kinder Gottes" bezeichnet. [95]

Darstellung

Zoroastrianismus

Während des frühen Parthianischen Reiches wurde Ahura Mazda visuell für die Anbetung vertreten. Diese Praxis endete zu Beginn des Sassanidenreiches. Der zoroastrische Ikonoklasmus, der auf das Ende der Partherzeit und den Beginn der Sassaniden zurückzuführen ist, beendet schließlich die Verwendung aller Bilder von Ahura Mazda in der Anbetung. Ahura Mazda wurde jedoch weiterhin durch eine würdige männliche Figur symbolisiert, die in der sassanischen Investitur steht oder zu Pferde steht.

Judentum

Zumindest verwenden einige Juden kein Bild für Gott, da Gott das unvorstellbare Wesen ist der nicht in materiellen Formen dargestellt werden kann. [97] In einigen Beispielen jüdischer Kunst wird jedoch manchmal Gott oder zumindest sein Eingreifen durch ein Hand Of God-Symbol angezeigt, das das Bad Kol darstellt ( wörtlich "Tochter einer Stimme") oder "Voice of God" [98]

Der brennende Busch, der nicht von den Flammen verzehrt wurde, wird im Buch Exodus als symbolische Darstellung von Gott beschrieben, als er erschien zu Moses. [99]

Christentum

Frühe Christen glaubten, dass die Worte des Evangeliums von Johannes 1:18: "Niemand hat Gott jemals gesehen" und zahlreiche andere Aussagen sollten nicht nur für Gott gelten, sondern auch für Gott alle Versuche der Darstellung Gottes. [100]

Spätere Darstellungen von Gott wird gefunden. Some, like the Hand of God, are depiction borrowed from Jewish art.

The beginning of the 8th century witnessed the suppression and destruction of religious icons as the period of Byzantine iconoclasm (literally image-breaking) started. The Second Council of Nicaea in 787 effectively ended the first period of Byzantine iconoclasm and restored the honouring of icons and holy images in general.[101] However, this did not immediately translate into large scale depictions of God the Father. Even supporters of the use of icons in the 8th century, such as Saint John of Damascus, drew a distinction between images of God the Father and those of Christ.

Prior to the 10th century no attempt was made to use a human to symbolize God the Father in Western art.[100] Yet, Western art eventually required some way to illustrate the presence of the Father, so through successive representations a set of artistic styles for symbolizing the Father using a man gradually emerged around the 10th century AD. A rationale for the use of a human is the belief that God created the soul of Man in the image of his own (thus allowing Human to transcend the other animals).

It appears that when early artists designed to represent God the Father, fear and awe restrained them from a usage of the whole human figure. Typically only a small part would be used as the image, usually the hand, or sometimes the face, but rarely a whole human. In many images, the figure of the Son supplants the Father, so a smaller portion of the person of the Father is depicted.[102]

By the 12th century depictions of God the Father had started to appear in French illuminated manuscripts, which as a less public form could often be more adventurous in their iconography, and in stained glass church windows in England. Initially the head or bust was usually shown in some form of frame of clouds in the top of the picture space, where the Hand of God had formerly appeared; the Baptism of Christ on the famous baptismal font in Liège of Rainer of Huy is an example from 1118 (a Hand of God is used in another scene). Gradually the amount of the human symbol shown can increase to a half-length figure, then a full-length, usually enthroned, as in Giotto's fresco of c. 1305 in Padua.[103] In the 14th century the Naples Bible carried a depiction of God the Father in the Burning bush. By the early 15th century, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry has a considerable number of symbols, including an elderly but tall and elegant full-length figure walking in the Garden of Eden, which show a considerable diversity of apparent ages and dress. The "Gates of Paradise" of the Florence Baptistry by Lorenzo Ghiberti, begun in 1425 use a similar tall full-length symbol for the Father. The Rohan Book of Hours of about 1430 also included depictions of God the Father in half-length human form, which were now becoming standard, and the Hand of God becoming rarer. At the same period other works, like the large Genesis altarpiece by the Hamburg painter Meister Bertram, continued to use the old depiction of Christ as Logos in Genesis scenes. In the 15th century there was a brief fashion for depicting all three persons of the Trinity as similar or identical figures with the usual appearance of Christ.

In an early Venetian school Coronation of the Virgin by Giovanni d'Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini (c. 1443), The Father is depicted using the symbol consistently used by other artists later, namely a patriarch, with benign, yet powerful countenance and with long white hair and a beard, a depiction largely derived from, and justified by, the near-physical, but still figurative, description of the Ancient of Days.[104]

. ...the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire. (Daniel 7:9)

In the Annunciation by Benvenuto di Giovanni in 1470, God the Father is portrayed in the red robe and a hat that resembles that of a Cardinal. However, even in the later part of the 15th century, the symbolic representation of the Father and the Holy Spirit as "hands and dove" continued, e.g. in Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ in 1472.[105]

In Renaissance paintings of the adoration of the Trinity, God may be depicted in two ways, either with emphasis on The Father, or the three elements of the Trinity. The most usual depiction of the Trinity in Renaissance art depicts God the Father using an old man, usually with a long beard and patriarchal in appearance, sometimes with a triangular halo (as a reference to the Trinity), or with a papal crown, specially in Northern Renaissance painting. In these depictions The Father may hold a globe or book (to symbolize God's knowledge and as a reference to how knowledge is deemed divine). He is behind and above Christ on the Cross in the Throne of Mercy iconography. A dove, the symbol of the Holy Spirit may hover above. Various people from different classes of society, e.g. kings, popes or martyrs may be present in the picture. In a Trinitarian Pietà, God the Father is often symbolized using a man wearing a papal dress and a papal crown, supporting the dead Christ in his arms. They are depicted as floating in heaven with angels who carry the instruments of the Passion.[106]

Representations of God the Father and the Trinity were attacked both by Protestants and within Catholicism, by the Jansenist and Baianist movements as well as more orthodox theologians. As with other attacks on Catholic imagery, this had the effect both of reducing Church support for the less central depictions, and strengthening it for the core ones. In the Western Church, the pressure to restrain religious imagery resulted in the highly influential decrees of the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563. The Council of Trent decrees confirmed the traditional Catholic doctrine that images only represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person, not the image.[107]

Artistic depictions of God the Father were uncontroversial in Catholic art thereafter, but less common depictions of the Trinity were condemned. In 1745 Pope Benedict XIV explicitly supported the Throne of Mercy depiction, referring to the "Ancient of Days", but in 1786 it was still necessary for Pope Pius VI to issue a papal bull condemning the decision of an Italian church council to remove all images of the Trinity from churches.[108]

God the Father is symbolized in several Genesis scenes in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, most famously The Creation of Adam (whose image of near touching hands of God and Adam is iconic of humanity, being a reminder that Man is created in the Image and Likeness of God (Gen 1:26)).God the Father is depicted as a powerful figure, floating in the clouds in Titian's Assumption of the Virgin in the Frari of Venice, long admired as a masterpiece of High Renaissance art.[109] The Church of the Gesù in Rome includes a number of 16th-century depictions of God the Father. In some of these paintings the Trinity is still alluded to in terms of three angels, but Giovanni Battista Fiammeri also depicted God the Father as a man riding on a cloud, above the scenes.[110]

In both the Last Judgment and the Coronation of the Virgin paintings by Rubens he depicted God the Father using the image that by then had become widely accepted, a bearded patriarchal figure above the fray. In the 17th century, the two Spanish artists Diego Velázquez (whose father-in-law Francisco Pacheco was in charge of the approval of new images for the Inquisition) and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo both depicted God the Father using a patriarchal figure with a white beard in a purple robe.

While representations of God the Father were growing in Italy, Spain, Germany and the Low Countries, there was resistance elsewhere in Europe, even during the 17th century. In 1632 most members of the Star Chamber court in England (except the Archbishop of York) condemned the use of the images of the Trinity in church windows, and some considered them illegal.[111] Later in the 17th century Sir Thomas Browne wrote that he considered the representation of God the Father using an old man "a dangerous act" that might lead to Egyptian symbolism.[112] In 1847, Charles Winston was still critical of such images as a "Romish trend" (a term used to refer to Roman Catholics) that he considered best avoided in England.[113]

In 1667 the 43rd chapter of the Great Moscow Council specifically included a ban on a number of symbolic depictions of God the Father and the Holy Spirit, which then also resulted in a whole range of other icons being placed on the forbidden list,[114][115] mostly affecting Western-style depictions which had been gaining ground in Orthodox icons. The Council also declared that the person of the Trinity who was the "Ancient of Days" was Christ, as Logosnot God the Father. However some icons continued to be produced in Russia, as well as Greece, Romania, and other Orthodox countries.

Islam

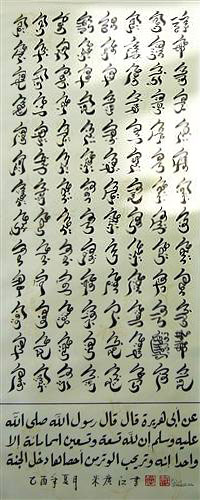

Muslims believe that God (Allah) is beyond all comprehension and equal, and does not resemble any of his creations in any way. Thus, Muslims are not iconodules, are not expected to visualize God, and instead of having pictures of Allah in their mosques, have religious scripts written on the wall.[35]

Bahá'í Faith

Bahá'u'lláh taught that God is directly unknowable to common mortals, but that his attributes and qualities can be indirectly known by learning from and imitating his divine Manifestations, which in Bahá'í theology are somewhat comparable to Hindu avatars or Abrahamic prophets. These Manifestations are the great prophets and teachers of many of the major religious traditions. These include Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, Zoroaster, Muhammad, Bahá'ú'lláh, and others. Although the faith is strictly monotheistic, it also preaches the unity of all religions and focuses on these multiple epiphanies as necessary for meeting the needs of humanity at different points in history and for different cultures, and as part of a scheme of progressive revelation and education of humanity.

Theological approaches

Classical theists (such as Ancient Greco-Medieval philosophers, Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox Christians, much of Jews and Muslims, and some Protestants) speak of God as a divinely simple “nothing” that is completely transcendent (totally independent of all else), and having attributes such as immutability, impassibility, and timelessness.[116]Theologians of theistic personalism (the view held by Rene Descartes, Isaac Newton, Alvin Plantinga, Richard Swinburne, William Lane Craig, and most modern evangelicals) argue that God is most generally the ground of all being, immanent in and transcendent over the whole world of reality, with immanence and transcendence being the contrapletes of personality.[117]Carl Jung equated religious ideas of God with transcendental metaphors of higher consciousness, in which God can be just as easily be imagined "as an eternally flowing current of vital energy that endlessly changes shape ... a s an eternally unmoved, unchangeable essence."[6]

The attributes of the God of classical theism were all claimed to varying degrees by the early Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars, including Maimonides,[48]St Augustine,[48] and Al-Ghazali.[118]

Many philosophers developed arguments for the existence of God,[8] while attempting to comprehend the precise implications of God's attributes. Reconciling some of those attributes-particularly the attributes of the God of theistic personalism- generated important philosophical problems and debates. For example, God's omniscience may seem to imply that God knows how free agents will choose to act. If God does know this, their ostensible free will might be illusory, or foreknowledge does not imply predestination, and if God does not know it, God may not be omniscient.[119]

The last centuries of philosophy have seen vigorous questions regarding the arguments for God's existence raised by such philosophers as Immanuel Kant, David Hume and Antony Flew, although Kant held that the argument from morality was valid. The theist response has been either to contend, as does Alvin Plantinga, that faith is "properly basic", or to take, as does Richard Swinburne, the evidentialist position.[120] Some theists agree that only some of the arguments for God's existence are compelling, but argue that faith is not a product of reason, but requires risk. There would be no risk, they say, if the arguments for God's existence were as solid as the laws of logic, a position summed up by Pascal as "the heart has reasons of which reason does not know."[121]

Many religious believers allow for the existence of other, less powerful spiritual beings such as angels, saints, jinn, demons, and devas.[122][123][124][125][126]

See also

References

- ^ Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe (1959)

- ^ Proclus, The Six Books of Proclus, the Platonic Successor, on the Theology of Plato Tr. Thomas Taylor (1816) Vol. 2, Ch. 2, "Of Plato"

- ^ a b c d Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)The Oxford Companion to PhilosophyOxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ David Bordwell (2002). Catechism of the Catholic ChurchContinuum International Publishing ISBN 978-0-86012-324-8 p. 84

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ a b Jung, Carl (1976) [1971]. "Answer to Job". In Joseph Campbell. The Portable Jung. Pinguin-Bücher. pp. 522–23. ISBN 978-0-14-015070-4.

- ^ "G-d has no body, no genitalia, therefore the very idea that G-d is male or female is patently absurd. Although in the Talmudic part of the Torah and especially in Kabalah G-d is referred to under the name 'Sh'chinah' – which is feminine, this is only to accentuate the fact that all the creation and nature are actually in the receiving end in reference to the creator and as no part of the creation can perceive the creator outside of nature, it is adequate to refer to the divine presence in feminine form. We refer to G-d using masculine terms simply for convenience's sake, because Hebrew has no neutral gender; G-d is no more male than a table is." Judaism 101. "The fact that we always refer to God as 'He' is also not meant to imply that the concept of sex or gender applies to God." Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, The Aryeh Kaplan ReaderMesorah Publications (1983), p. 144

- ^ a b c Platinga, Alvin. "God, Arguments for the Existence of", Routledge Encyclopedia of PhilosophyRoutledge, 2000.

- ^ Jan Assmann, Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten StudiesStanford University Press 2005, p. 59

- ^ M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian LiteratureVol. 2, 1980, p. 96

- ^ Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity – p. 136, Michael P. Levine – 2002

- ^ A Feast for the Soul: Meditations on the Attributes of God : ... – p. x, Baháʾuʾlláh, Joyce Watanabe – 2006

- ^ Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism – p. ix, Kartar Singh Duggal – 1988

- ^ McDaniel, June (2013), A Modern Hindu Monotheism: Indonesian Hindus as ‘People of the Book’. The Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/jhs/hit030

- ^ The Intellectual Devotional: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Roam confidently with the cultured class, David S. Kidder, Noah D. Oppenheim, p. 364

- ^ a b Alan H. Dawe (2011). The God Franchise: A Theory of Everything. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-473-20114-2.

Pandeism: This is the belief that God created the universe, is now one with it, and so, is no longer a separate conscious entity. This is a combination of pantheism (God is identical to the universe) and deism (God created the universe and then withdrew Himself).

- ^ Christianity and Other Religionsby John Hick and Brian Hebblethwaite. 1980. p. 178.

- ^ The ulterior etymology is disputed. Apart from the unlikely hypothesis of adoption from a foreign tongue, the OTeut. "ghuba" implies as its preTeut-type either "*ghodho-m" or "*ghodto-m". The former does not appear to admit of explanation; but the latter would represent the neut. pple. of a root "gheu-". There are two Aryan roots of the required form ("*g,heu-" with palatal aspirate) one with meaning 'to invoke' (Skr. "hu") the other 'to pour, to offer sacrifice' (Skr "hu", Gr. χεηi;ν, OE "geotàn" Yete v). OED Compact Edition, G, p. 267

- ^ Barnhart, Robert K. (1995). The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology: the Origins of American English Wordsp. 323. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-270084-7

- ^ "'God' in Merriam-Webster (online)". Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ Webster's New World Dictionary; "God n. ME < OE, akin to Ger gott, Goth guth, prob. < IE base * ĝhau-, to call out to, invoke > Sans havaté, (he) calls upon; 1. any of various beings conceived of as supernatural, immortal, and having special powers over the lives and affairs of people and the course of nature; deity, esp. a male deity: typically considered objects of worship; 2. an image that is worshiped; idol 3. a person or thing deified or excessively honored and admired; 4. [G-] in monotheistic religions, the creator and ruler of the universe, regarded as eternal, infinite, all-powerful, and all-knowing; Supreme Being; the Almighty"

- ^

Dictionary.com; "God /gɒd/ noun: 1. the one Supreme Being, the creator and ruler of the universe. 2. the Supreme Being considered with reference to a particular attribute. 3. (lowercase) one of several deities, esp. a male deity, presiding over some portion of worldly affairs. 4. (often lowercase) a supreme being according to some particular conception: the God of mercy. 5. Christian Science. the Supreme Being, understood as Life, Truth, Love, Mind, Soul, Spirit, Principle. 6. (lowercase) an image of a deity; an idol. 7. (lowercase) any deified person or object. 8. (often lowercase) Gods, Theater. 8a. the upper balcony in a theater. 8b. the spectators in this part of the balcony." - ^ Barton, G.A. (2006). A Sketch of Semitic Origins: Social and Religious. Kessinger Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4286-1575-5.

- ^ "God". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- ^ "Islam and Christianity", Encyclopedia of Christianity (2001): Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews also refer to God as Allāh.

- ^ L. Gardet. "Allah". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

- ^ Hastings 2003, p. 540

- ^ Froese, Paul; Christopher Bader (Fall–Winter 2004). "Does God Matter? A Social-Science Critique". Harvard Divinity Bulletin. 4. 32.

- ^ See Swami Bhaskarananda, Essentials of Hinduism (Viveka Press 2002) ISBN 1-884852-04-1

- ^ "Sri Guru Granth Sahib". Sri Granth. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ "What Is the Trinity?". Archived from the original on 2014-02-19.

- ^ Quran 112:1–4

- ^ D. Gimaret. "Allah, Tawhid". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ a b Robyn Lebron (2012). Searching for Spiritual Unity...Can There Be Common Ground?. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4627-1262-5.

- ^ Müller, Max. (1878) Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion: As Illustrated by the Religions of India. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ a b Smart, Jack; John Haldane (2003). Atheism and Theism. Blackwell Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-631-23259-9.

- ^ a b Lemos, Ramon M. (2001). A Neomedieval Essay in Philosophical Theology. Lexington-Bücher. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7391-0250-3.

- ^ "Philosophy of Religion.info – Glossary – Theism, Atheism, and Agonisticism". Philosophy of Religion.info. Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ "Theism – definition of theism by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Sean F. Johnston (2009). The History of Science: A Beginner's Guide. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-85168-681-0.

In its most abstract form, deism may not attempt to describe the characteristics of such a non-interventionist creator, or even that the universe is identical with God (a variant known as pandeism).

- ^ Paul Bradley (2011). This Strange Eventful History: A Philosophy of Meaning. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-87586-876-9.

Pandeism combines the concepts of Deism and Pantheism with a god who creates the universe and then becomes it.

- ^ a b Allan R. Fuller (2010). Thought: The Only Reality. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60844-590-5.

Pandeism is another belief that states that God is identical to the universe, but God no longer exists in a way where He can be contacted; therefore, this theory can only be proven to exist by reason. Pandeism views the entire universe as being from God and now the universe is the entirety of God, but the universe at some point in time will fold back into one single being which is God Himself that created all. Pandeism raises the question as to why would God create a universe and then abandon it? As this relates to pantheism, it raises the question of how did the universe come about what is its aim and purpose?

- ^ Peter C. Rogers (2009). Ultimate Truth, Book 1. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-4389-7968-7.

As with Panentheism, Pantheism is derived from the Greek: 'pan'= all and 'theos' = God, it literally means "God is All" and "All is God." Pantheist purports that everything is part of an all-inclusive, indwelling, intangible God; or that the Universe, or nature, and God are the same. Further review helps to accentuate the idea that natural law, existence, and the Universe which is the sum total of all that is, was, and shall be, is represented in the theological principle of an abstract 'god' rather than an individual, creative Divine Being or Beings of any kind. This is the key element which distinguishes them from Panentheists and Pandeists. As such, although many religions may claim to hold Pantheistic elements, they are more commonly Panentheistic or Pandeistic in nature.

- ^ John Culp (2013). "Panentheism," Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophySpring.

- ^ The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky pp. 259–61

- ^ Henry, Michel (2003). I am the Truth. Toward a philosophy of Christianity. Translated by Susan Emanuel. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3780-7.

- ^ a b c d Edwards, Paul. "God and the philosophers" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)The Oxford Companion to PhilosophyOxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-61592-446-2.

- ^ "A Plea for Atheism. By 'Iconoclast'", London, Austin & Co., 1876, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Dawkins, Richard (2006). The God Delusion. Great Britain: Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-618-68000-9.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2006-10-23). "Why There Almost Certainly Is No God". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1996). The Demon Haunted World. New York: Ballantine-Bücher. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-345-40946-1.

- ^ Stephen Hawking; Leonard Mlodinow (2010). The Grand Design. Bantam-Bücher. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-553-80537-6.

- ^ Hepburn, Ronald W. (2005) [1967]. "Agnosticism". In Donald M. Borchert. The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 1 (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference USA (Gale). p. 92. ISBN 978-0-02-865780-6.

In the most general use of the term, agnosticism is the view that we do not know whether there is a God or not.

(p. 56 in 1967 edition) - ^ Rowe, William L. (1998). "Agnosticism". In Edward Craig. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor und Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-07310-3.

In the popular sense, an agnostic is someone who neither believes nor disbelieves in God, whereas an atheist disbelieves in God. In the strict sense, however, agnosticism is the view that human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the belief that God does not exist. In so far as one holds that our beliefs are rational only if they are sufficiently supported by human reason, the person who accepts the philosophical position of agnosticism will hold that neither the belief that God exists nor the belief that God does not exist is rational.

- ^ "agnostic, agnosticism". OED Online, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press. 2012.

agnostic. : A. n[oun]. :# A person who believes that nothing is known or can be known of immaterial things, especially of the existence or nature of God. :# In extended use: a person who is not persuaded by or committed to a particular point of view; a sceptic. Also: person of indeterminate ideology or conviction; an equivocator. : B. adj[ective]. :# Of or relating to the belief that the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena is unknown and (as far as can be judged) unknowable. Also: holding this belief. :# a. In extended use: not committed to or persuaded by a particular point of view; sceptical. Also: politically or ideologically unaligned; non-partisan, equivocal. agnosticism n. The doctrine or tenets of agnostics with regard to the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena or to knowledge of a First Cause or God.

- ^ Nielsen 2013: "Instead of saying that an atheist is someone who believes that it is false or probably false that there is a God, a more adequate characterization of atheism consists in the more complex claim that to be an atheist is to be someone who rejects belief in God for the following reasons ... : for an anthropomorphic God, the atheist rejects belief in God because it is false or probably false that there is a God; for a nonanthropomorphic God ... because the concept of such a God is either meaningless, unintelligible, contradictory, incomprehensible, or incoherent; for the God portrayed by some modern or contemporary theologians or philosophers ... because the concept of God in question is such that it merely masks an atheistic substance—e.g., "God" is just another name for love, or ... a sym bolic term for moral ideals."

- ^ Edwards 2005: "On our definition, an 'atheist' is a person who rejects belief in God, regardless of whether or not his reason for the rejection is the claim that 'God exists' expresses a false proposition. People frequently adopt an attitude of rejection toward a position for reasons other than that it is a false proposition. It is common among contemporary philosophers, and indeed it was not uncommon in earlier centuries, to reject positions on the ground that they are meaningless. Sometimes, too, a theory is rejected on such grounds as that it is sterile or redundant or capricious, and there are many other considerations which in certain contexts are generally agreed to constitute good grounds for rejecting an assertion."

- ^ Rowe 1998: "As commonly understood, atheism is the position that affirms the nonexistence of God. So an atheist is someone who disbelieves in God, whereas a theist is someone who believes in God. Another meaning of 'atheism' is simply nonbelief in the existence of God, rather than positive belief in the nonexistence of God. ... an atheist, in the broader sense of the term, is someone who disbelieves in every form of deity, not just the God of traditional Western theology."

- ^ Boyer, Pascal (2001). Religion Explained. New York: Basic Books. pp. 142–243. ISBN 978-0-465-00696-0.

- ^ du Castel, Bertrand; Jurgensen, Timothy M. (2008). Computer Theology. Austin, Texas: Midori Press. pp. 221–22. ISBN 978-0-9801821-1-8.

- ^ Barrett, Justin (1996). "Conceptualizing a Nonnatural Entity: Anthropomorphism in God Concepts" (PDF).

- ^ Rossano, Matt (2007). "Supernaturalizing Social Life: Religion and the Evolution of Human Cooperation" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley, an English biologist, was the first to come up with the word agnostic in 1869 Dixon, Thomas (2008). Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-929551-7. However, earlier authors and published works have promoted an agnostic points of view. They include Protagoras, a 5th-century BCE Greek philosopher. "The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Protagoras (c. 490 – c. 420 BCE)". Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

While the pious might wish to look to the gods to provide absolute moral guidance in the relativistic universe of the Sophistic Enlightenment, that certainty also was cast into doubt by philosophic and sophistic thinkers, who pointed out the absurdity and immorality of the conventional epic accounts of the gods. Protagoras' prose treatise about the gods began 'Concerning the gods, I have no means of knowing whether they exist or not or of what sort they may be. Many things prevent knowledge including the obscurity of the subject and the brevity of human life.'

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas (1990). Kreeft, Peter, ed. Summa of the Summa. Ignatius Press. p. 63.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas (1990). Kreeft, Peter, ed. Summa of the Summa. Ignatius Press. pp. 65–69.

- ^ Curley, Edwin M. (1985). The Collected Works of Spinoza. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07222-7.

- ^ Nadler, Steven (2001-06-29). "Baruch Spinoza".

- ^ Snobelen, Stephen D. (1999). "Isaac Newton, heretic : the strategies of a Nicodemite" (PDF). British Journal for the History of Science. 32 (4): 381–419. doi:10.1017/S0007087499003751. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ^ Webb, R.K. ed. Knud Haakonssen. "The emergence of Rational Dissent." Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in eighteenth-century Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1996. p19.

- ^ Newton, 1706 Opticks (2nd Edition), quoted in H.G. Alexander 1956 (ed): The Leibniz-Clarke correspondenceUniversity of Manchester Press.

- ^ "SUMMA THEOLOGIAE: The existence of God (Prima Pars, Q. 2)". Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Summa of Theology I, q. 2, The Five Ways Philosophers Have Proven God's Existence

- ^ Alister E. McGrath (2005). Dawkins' God: genes, memes, and the meaning of life. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2539-0.

- ^ Floyd H. Barackman (2001). Practical Christian Theology: Examining the Great Doctrines of the Faith. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-2380-2.

- ^ Gould, Stephen J. (1998). Leonardo's Mountain of Clams and the Diet of Worms. Jonathan Cape. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-224-05043-2.

- ^ Krauss L. A Universe from Nothing. Free Press, New York. 2012. ISBN 978-1-4516-2445-8

- ^ Harris, S. The end of faith. W.W. Norton and Company, New York. 2005. ISBN 0-393-03515-8

- ^ Culotta, E (2009). "The origins of religion". Wissenschaft . 326 (5954): 784–87. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..784C. doi:10.1126/science.326_784. PMID 19892955.

- ^ "Audio Visual Resources". Ravi Zacharias International Ministries. Archived from the original on 2007-03-29. Retrieved 2007-04-07.includes sound recording of the Dawkins-McGrath debate

- ^ Francis Schüssler Fiorenza and Gordon D. Kaufman, "God", Ch 6, in Mark C. Taylor, ed, Critical Terms for Religious Studies (University of Chicago, 1998/2008), 136–40.

- ^ Gen. 17:1; 28:3; 35:11; Ex. 6:31; Ps. 91:1, 2

- ^ Gen. 14:19; Ps. 9:2; Dan. 7:18, 22, 25

- ^ Bentley, David (1999). The 99 Beautiful Names for God for All the People of the Book. William Carey Library. ISBN 978-0-87808-299-5.

- ^ Ramsay, Tamasin (September 2010). "Custodians of Purity An Ethnography of the Brahma Kumaris". Monash University: 107–08.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas (1274). Summa Theologica. Part 1, Question 3, Article 1.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo (397). Confessions. Book 7.

- ^ Lang, David; Kreeft, Peter (2002). Why Matter Matters: Philosophical and Scriptural Reflections on the Sacraments. Chapter Five: Why Male Priests?: Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 978-1-931709-34-7.

- ^ Elaine H. Pagels "What Became of God the Mother? Conflicting Images of God in Early Christianity" Signs, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Winter, 1976), pp. 293–303

- ^ Coogan, Michael (2010). "6. Fire in Divine Loins: God's Wives in Myth and Metaphor". God and Sex. What the Bible Really Says (1st ed.). New York, Boston: Twelve. Hachette Book Group. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-446-54525-9. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

humans are modeled on elohimspecifically in their sexual differences.

- ^ "Human Nature and the Purpose of Existence". Patheos.com. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- ^ Quran 51:56

- ^ "Allah would replace you with a people who sin". islamtoday.net. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ McGrath, Alister (2006). Christian Theology: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-4051-5360-7.

- ^ "International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Sons of God (New Testament)". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Moses – Hebrew prophet". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ A matter disputed by some scholars

- ^ Exodus 3:1–4:5

- ^ a b James Cornwell, 2009 Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art ISBN 0-8192-2345-X p. 2

- ^ Edward Gibbon, 1995 The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire ISBN 0-679-60148-1 p. 1693

- ^ Adolphe Napoléon Didron, 2003 Christian iconography: or The history of Christian art in the middle ages ISBN 0-7661-4075-X p. 169

- ^ Arena Chapel, at the top of the triumphal arch, God sending out the angel of the Annunciation. See Schiller, I, fig 15

- ^ Bigham Chapter 7

- ^ Arthur de Bles, 2004 How to Distinguish the Saints in Art by Their Costumes, Symbols and Attributes ISBN 1-4179-0870-X p. 32

- ^ Irene Earls, 1987 Renaissance art: a topical dictionary ISBN 0-313-24658-0 pp. 8, 283

- ^ "CT25". Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Bigham, 73–76

- ^ Louis Lohr Martz, 1991 From Renaissance to baroque: essays on literature and art ISBN 0-8262-0796-0 p. 222

- ^ Gauvin Alexander Bailey, 2003 Between Renaissance and Baroque: Jesuit art in Rome ISBN 0-8020-3721-6 p. 233

- ^ Charles Winston, 1847 An Inquiry Into the Difference of Style Observable in Ancient Glass Paintings, Especially in England ISBN 1-103-66622-3, (2009) p. 229

- ^ Sir Thomas Browne's Works, 1852, ISBN 0-559-37687-1, 2006 p. 156

- ^ Charles Winston, 1847 An Inquiry Into the Difference of Style Observable in Ancient Glass Paintings, Especially in England ISBN 1-103-66622-3, (2009) p. 230

- ^ Oleg Tarasov, 2004 Icon and devotion: sacred spaces in Imperial Russia ISBN 1-86189-118-0 p. 185

- ^ "Council of Moscow – 1666–1667". Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ 1998, God, concepts of, Edward Craig, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Taylor & Francis, [1]

- ^ www.ditext.com

- ^ Plantinga, Alvin. "God, Arguments for the Existence of", Routledge Encyclopedia of PhilosophyRoutledge, 2000.

- ^ Wierenga, Edward R. "Divine foreknowledge" in Audi, Robert. The Cambridge Companion to Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- ^ Beaty, Michael (1991). "God Among the Philosophers". The Christian Century. Archived from the original on 2007-01-09. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Pascal, Blaise. Pensées1669.

- ^ Tuesday, December 8, 2009 (December 8, 2009). "More Americans Believe in Angels than Global Warming". Outsidethebeltway.com. Retrieved 2012-12-04.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Van, David (2008-09-18). "Guardian Angels Are Here, Say Most Americans". Time. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ "Poll: Nearly 8 in 10 Americans believe in angels". CBS-Nachrichten. December 23, 2011. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ Salmon, Jacqueline L. "Most Americans Believe in Higher Power, Poll Finds". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ Qur'an 15:27

Further reading

- Pickover, Cliff, The Paradox of God and the Science of OmnisciencePalgrave/St Martin's Press, 2001. ISBN 1-4039-6457-2

- Collins, Francis, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for BeliefFree Press, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-8639-1

- Miles, Jack, God: A BiographyVintage, 1996. ISBN 0-679-74368-5

- Armstrong, Karen, A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and IslamBallantine Books, 1994. ISBN 0-434-02456-2

- Paul Tillich, Systematic TheologyVol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951). ISBN 0-226-80337-6

- Hastings, James Rodney (1925–2003) [1908–26]. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. John A Selbie (Volume 4 of 24 (Behistun (continued) to Bunyan.) ed.). Edinburgh: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-7661-3673-1.

The encyclopedia will contain articles on all the religions of the world and on all the great systems of ethics. It will aim at containing articles on every religious belief or custom, and on every ethical movement, every philosophical idea, every moral practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment